“I just couldn’t help myself.”

I suspect we have all resorted to that excuse at one time or another. It is even an established courtroom defense, known as “irresistible impulse,” presented as a mitigating circumstance and a plea for mercy.

I was remembering this from my year in law school, aware of how difficult it is to resist an intense temptation. Or an urge to get even for an act of abuse.

Though I’ve never had to contend with a lurking nemesis like Moriarity to Sherlock Holmes, it struck me that someone in my life has bothered me since I was a kid. Oddly enough, he thinks of himself as my best friend, because admittedly we’re very close. He is my own Ego, and out of genuine admiration for his persuasive methods and relentless nature, I have named him with a capital E.

I owe the Ego my thanks for much of my motivation, yet he’s also the cause of most of the trouble I have gotten into. Even today he can catch me off guard when his counsel is what my urges are wanting to hear. “Trust me,” he says, “I know what you like and I’m here to help you get it.”

The Ego’s steady presence in my life raises a number of questions: Is he merely a mischief-maker that God has planted in me for amusement, or does he offer qualities that would serve me to develop? Am I stuck with him forever, or is there a way to lose him?

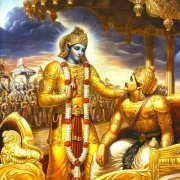

It turns out the Ego in history is an ancient player, whose origin dates to India’s epic saga, the Mahabharata. Long before he was known to Freud and others by his three-letter name, the Ego was born to royalty as Bhishma, the noblest of princes. His is a story of great inspiration…until one fateful choice led him to the side of delusion, thus leading us also into our own battle with it.

The Ego means well and would be glad if we never suffered from following its advice. But its perspective is finite, short-sighted and fleeting, sure to result in a measure of letdown or worse.

So, what are we to do? How are we to coexist without its influence messing things up? Our teachings and practices clearly offer more than the Ego can: lasting inner peace, love and joy. But the tasks they require us to undertake are huge, such as replacing what we want with wanting what we get, and serving others in the spirit of nishkam karma, non-attachment to the fruits of our labors.

A large part of our job in this life is to unlearn much of what we have been conditioned to accept. The more we do this, the more we gain against the Ego’s sway, for it has a nemesis too: our self-control. As we apply it, the Ego yields to its leash. Lifetimes more may be needed to undo its grip, but even the Ego itself, born of nobility that unwittingly went astray, secretly roots for its demise, the day it surrenders to the greater good of the soul. May we disidentify with it and help that happen.